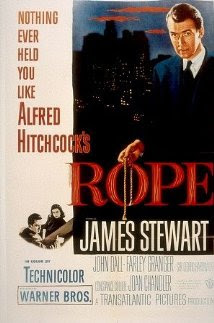

Hitchcock's nostalgia from the day before was still on. I was curious to re-watch another of his movies, one that is a hit on cinema's studies (My first proofreading job was a dissertation about this film). Rope is well known for its long shots, a difficult choice of filming in that time. I've seen it last some 10 years ago, but I've already had lost bits of this story about the cruelty and danger of ideas of superiority - the most harmful plague in humanity's history.

Hitchcock's nostalgia from the day before was still on. I was curious to re-watch another of his movies, one that is a hit on cinema's studies (My first proofreading job was a dissertation about this film). Rope is well known for its long shots, a difficult choice of filming in that time. I've seen it last some 10 years ago, but I've already had lost bits of this story about the cruelty and danger of ideas of superiority - the most harmful plague in humanity's history.James Stewart didn't like this movie, but I love him in it. His gradual realization of what was in fact happening under a dinner party on a luxury flat in NY is created without excess by his solid performance. His character lives in the world of ideas, but is confronted with his own beliefs in a horrendous act. John Dall reminds Ben Affleck, both sharing a striking resemblance to a rat (It is truly annoying), so it wasn't difficult to me to despise him from the beginning. The snobbish features of some characters are so well represented by this actor, and also by the dialogue, that the conclusion is a coherent way to finish this tale about the futile cruelty of men that thing they are better than their peers.

Ps: There's a whimsical dialogue about a movie with Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman with a one word title - it is probably Notorious, but the old lady is not able to remember it - actually, she couldn't remember the name of anything (she's worse than me).

FRANÇOIS TRUFFAUT. Rope was made in 1948. In several respects this picture is a milestone in your career. For one thing, you produced it; for another, it was your first color film; and finally,· it represented an enormous technical challenge. Is the screenplay very different from Patrick Hamilton's stage play?

ALFRED HITCHCOCK. No, not really. Arthur Laurents did the screenplay and Hume Cronyn worked with me on the adaptation. The dialogue was partly from the original play and partly by Laurents. I undertook Rope as a stunt; that's the only way I can describe it. I really don't know how I came to indulge in it. The stage drama was played out in the actual time of the story; the action is continuous from the moment the curtain goes up until it comes down again. I asked myself whether it was technically possible to film it in the same way. The only way to achieve that, I found, would be to handle the shooting in the same continuous action, with no break in the telling of a story that begins at seven-thirty and ends at nine-fifteen. And I got this crazy idea to do it in a single When I look back, I realize that it was quite nonsensical because I was breaking with my own theories on the importance of cutting and montage for the visual narration of a story. On the other hand, this film was, in a sense, precut. The mobility of the camera and the movement of the players closely followed my usual cutting practice. In other words, I maintained the rule of varying the size of the image in relation to its emotional importance within a given episode. Naturally, we went to a lot of trouble to achieve this; and the difficulties went beyond our problems with the camera. Since the action starts in broad daylight and ends by nightfall, we had to deal with the gradual darkening of the background by altering the flow of light between seven-thirty and nine-fifteen. To maintain that continuous action, with no dissolves and no time lapses, there were other technical snags to overcome, among them, how to reload the camera at the end of each reel without interrupting the scene. We handled that by having a figure pass in front of the camera, blacking out the action very briefly while we changed from one camera to the other. In that way we'd end on a close-up of someone's jacket, and at the beginning of the next reel, we'd open with the same close-up of the same character.

F.T. Aside from all of this, I imagine that the fact that you were using color for the first time must have added to your difficulties.

A.H. Yes. Because I was determined to reduce the color to a minimum. We had built the set of an apartment, consisting of a living room, a hallway, and a section of a kitchen. The picture overlooked the New York skyline, and we had that background made up in a semicircular pattern, so that the camera might swing around the room. To show that in proper perspective, that background was three times the size of the apartment decor itself. And between the set and the skyscrapers, we had some cloud formations made of spun glass. Each cloud was separate and mobile; some were hung on invisible wires and others were on stands, and they were also set in a semicircular pattern. We had a special working plan designed for the clouds, and between re~ls they were shifted from left to right. They were never actually shown in motion, but you must remember that the camera wasn't always on the window, so whenever we changed the reels, the stagehands would shift each cloud into the position designated on our working plan. And as soon as a cloud reached the edge of the horizon, it would be taken off and another one would appear in view of the window at the other side.

F.T. What about the problems with the color?

A.H. Toward the last four or five reels, in other words, by sunset, I realized that the or ange in the sun was far too strong, and on ac count of that we did the last five reels all over again. We now have to digress a little to talk about color. The average cameraman is a very fine techni cian. He can make a woman look beautiful; he can create natural lighting that is effective without being exaggerated. But there is often a problem that stems purely from the cameraman's artistic taste. Does he have a sense of color and does he use good taste in his choice of colors? Now, the cameraman who handled the lighting on Rope simply said to himself, "Well, it's just another sunset." Obviously, he hadn't looked at one for a long time, if ever at all, and what he did was completely unacceptable; it was like a lurid postcard. Joseph Valentine, who photographed Rope, had also worked on Shadow ofa Doubt. When I saw the initial rushes, my first feeling was that things show up much more in color than in black and white. And I discovered that it was the general practice to use the same lighting for color as for black and white. Now, as I've already told you, I especially admired the approach to lighting used by the Americans in 1920 because it overcame the two-dimensional nature of the image by separating the actor from the background through the use of backlights-they call them liners-to detach him from his setting. Now in color there is no need for this, unless the actor should happen to be dressed in the same color as the background, but that's highly improbable. It sounds elementary, doesn't it, and yet that's the tradition, and it's quite hard to break away from it. Surely, now that we work in color, we shouldn't be made aware of the source of the studio lighting. And yet, in many pictures, you will find people walking through the supposedly dingy corridors between the stage and dressing rooms of a theater, and because the scene is lighted by studio arc lamps, their shadows on the wall are black as coal. You just can't help wondering where those lights could possibly be coming from. Lending some books to the father of his victim, John Dall ties them with the cord he used to kill his friend. I truly believe that the problem of the lighting in color films has not yet been solved. I tried for the first time to change the style of color lighting in Torn Curtain. Jack Warren, who was on Re becca and Spellbound with me, is the camera man who cooperated. We must bear in mind that, fundamentally, there's no such thing as color; in fact, there's no such thing as a face, because until the light hits it, it is nonexistent. After all, one of the first things I learned in the School of Art was that there is no such thing as a line; there's only the light and the shade. On my first day in school I did a drawing; it was quite a good drawing, but because I was drawing with lines, it was totally incorrect and the error was immediately pointed out to me. Going back to Rope, there's a little sidelight. After four or five days the cameraman went off "sick." So I wound up with a Technicolor con sultant, and he completed the job with the help of the chief electrician.

F.T. What about the problems of a mobile camera?

A.H. Well, the technique of the camera movements was worked out, in its slightest details, well beforehand. We used a dolly and we mapped out our course through tiny numbers all over the floor, which served as guide marks. All the dollyman had to do was to get his camera on position Number One or Number Two at a given cue of the dialogue, then dolly over to the next number. When we went from one room into another, the wall of the hallway or of the living room would swing back on silent rails. And the furniture was mounted on rollers so that we could push it aside as the camera passed. It was an amazing thing to see a shot taken.

F.T. What is truly remarkable is that all of this was done so silently that you were able to make a direct sound track. For a European, particularly if he works in Rome or Paris, that's almost inconceivable.

A.H. They'd never done it in Hollywood either! To do it, we had a special floor made. The opening scene, you will recall, shows two young fellows strangling a man and putting his body into a chest. There was some dialogue. Then there is more dialogue as they go into the dining room and then to the kitchen. Walls are being moved and lights are being raised and lowered. I was so scared that something would go wrong that I couldn't even look during the first take. For eight minutes of consecutive shooting everything went very smoothly. Then the camera panned around as the two killers walked back toward the chest, and there, right in camera focus, was an electrician standing by the window! So the first take was ruined.

F.T. That raises a point I'm curious about. How many takes were there for each reel that was completed? In other words, how many takes were interrupted and how many did you complete?

A.H. Well, there were ten days of rehearsal with the cameras, the actors, and the lighting. Then there were eighteen days of shooting, including the nine days in which we did the retakes because of that orange sun I told you about.

F.T. Eighteen days of shooting. That would mean that the work on six of those days was totally useless. Were you ever able to complete two whole reels in a single day?

A.H. No, I don't think so.

F.T. In any case, I don't agree that Rope should be dismissed as a foolish experiment, particularly when you look at it in the context of your whole career: a director is tempted by the dream of linking all of a film's components into a single, continuous action. In this sense, it's a positive step in your evolution. Nevertheless, weighing the pros and cons-and the practices of all the great directors.who have considered the question seem to bear this outit is true that the classical cutting techniques dating back to D. W. Griffith have stood the test of time and still prevail today. Don't you agree?

A.H. No doubt about it; films must be cut. As an experiment, Rope may be forgiven, but it was definitely a mistake when I insisted on applying the same techniques to Under Capricorn.

F.T. Before winding up our discussion of Rope, one remarkable aspect is the painstaking quest for realism. The sound track of that picture is fantastically realistic, in particular, toward the end, when James Stewart opens the window to fire a shot in the night and one hears the noises gradually rising from the street.

A.H. You put it very correctly when you referred to the rise of the noises from the street. As a matter of fact, to get that effect, I made them put the microphone six stories high and I gathered a group of people below on the sidewalk and had them talk about the shots. As for the police siren, they told me they had one in the sound library. I asked them, "How are you going to give the impression of distance?" and they answered, "We'll make it soft at first, and then we'll bring it up loud." But I didn't want it done that way. I made them get an ambulance with a siren. We placed a microphone at the studio gate and sent the ambulance two miles away and that's the way we made the sound track.

F.T. Rope was the first film you produced. Was it financially rewarding?

A.H. Yes, that part was all right, and it had good notices. It cost about a million and a half dollars to make because so many things in it were being done for the first time. James Stewart was paid three hundred thousand dollars. M-G-M bought the rights a little while ago and they reissued the picture.

(TRUFFAUT, François. Hitchcock/Truffaut. Simon & Schuster, 1985, p, 179-184- with the collaboration of Hellen G. Scott).

As I've been adding old movies to my watch list, I watched a few of Hitchcock's films over the past year, and it's been a great experience. I hadn't heard of this one before, so I must say, after reading your post, I'm intrigued by it. Very much so. I'm curious about the more lengthy shots – that's something that I find fascinating in filmmaking, rather it's shot on film or digital (I don't know if you've seen Hunger, by Steve McQueen, but there's a scene in it where Michael Fassbander's character has a complex dialogue with a Priest for about 17 minutes in a single take! It's breathtaking: https://youtu.be/VAkBz9glJFo).

ReplyDeleteBut you also left me curious about the themes of Rope. After all, it can't be all about technique, as you pointed out. Should watch this one soon.

[ j ]